BODY AND SOUL COVERS THE WATERFRONT OF THIRTIES AND FORTIES JAZZ AND SWING, BLUES, BROADWAY, POPULAR SONG, COUNTRY, FOLK, RHYTHM & BLUES, FILM MUSIC, AND MORE. ANDY MILES HOSTS.

WHY A SHOW ABOUT THE THIRTIES AND FORTIES? SCROLL DOWN BELOW EPISODES AND FIND OUT.

EPISODES

Featuring Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Mildred Bailey, Xavier Cugat, Artie Shaw, music from two Academy Award-winning films, and more.

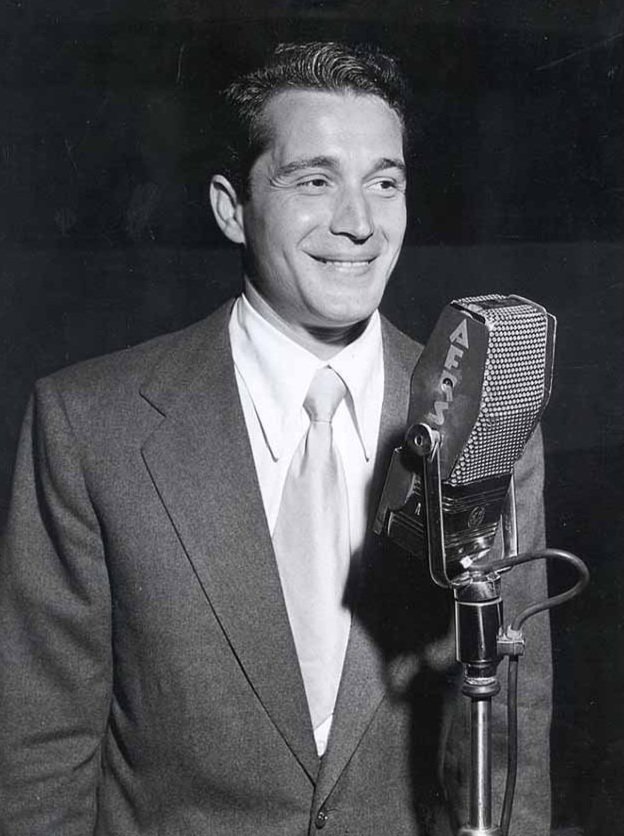

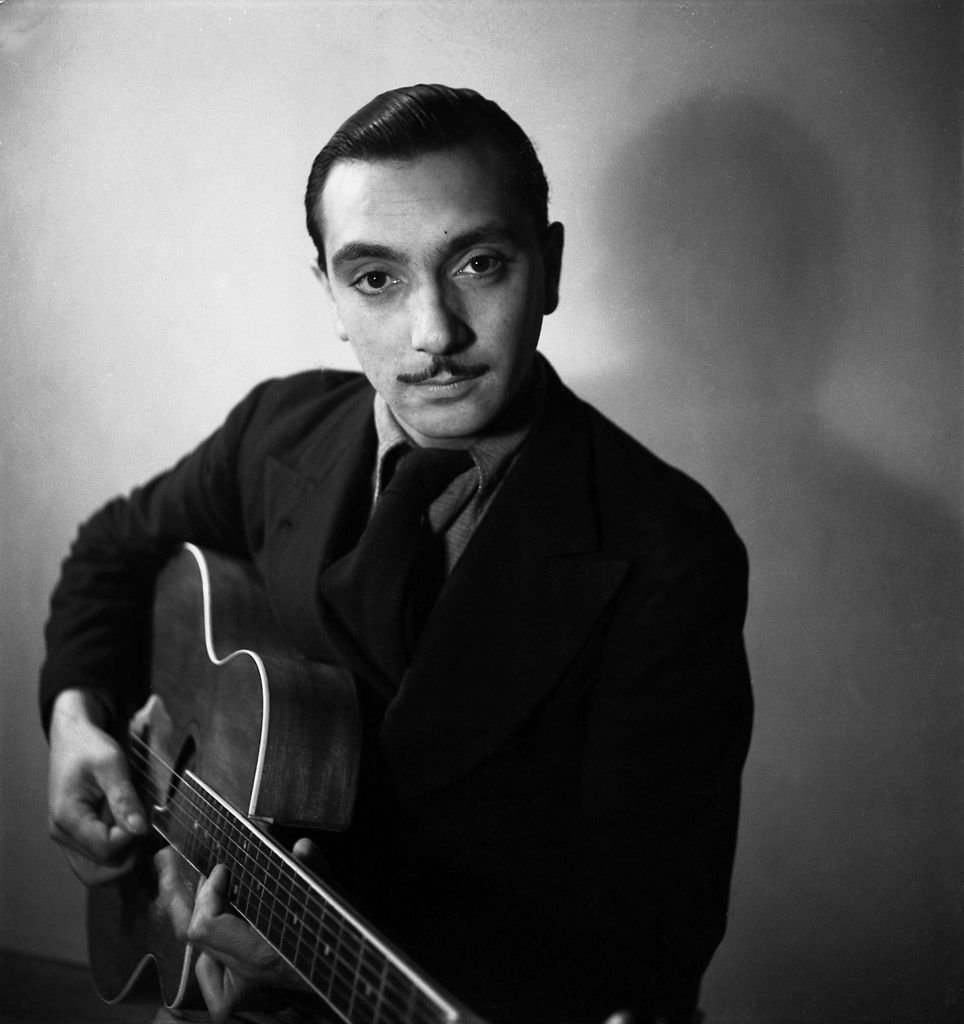

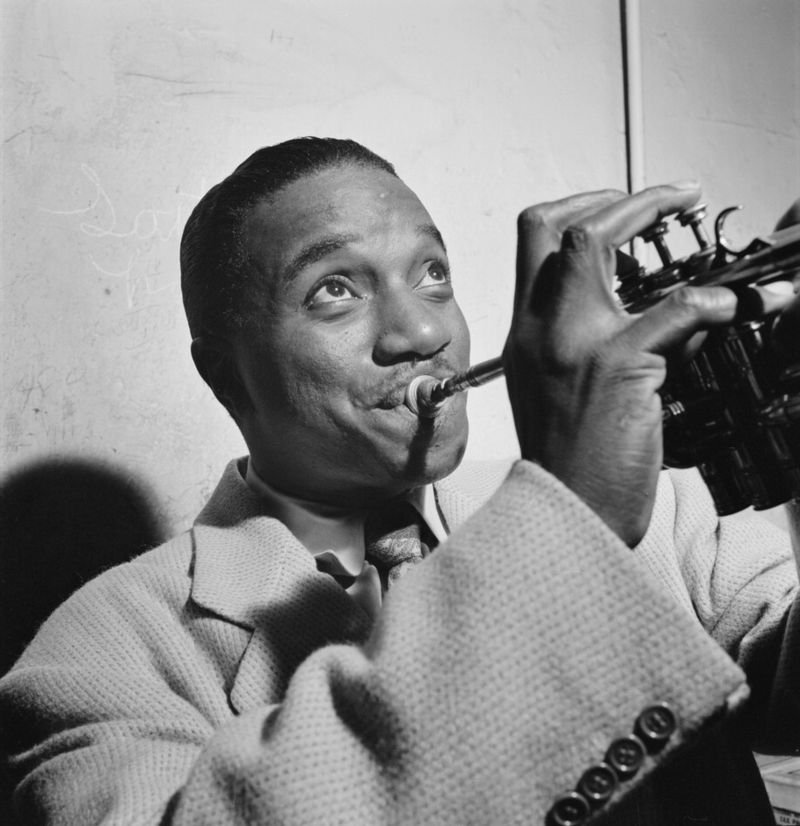

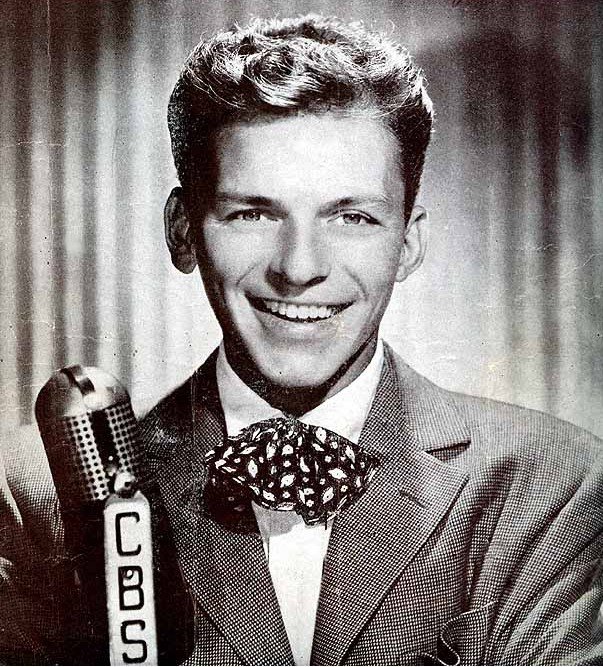

Featuring Django Reinhardt, Peggy Lee, The Mills Brothers, Frank Sinatra, music from the film “Laura” and the Broadway musical “Carousel,” and more.

Featuring Mahalia Jackson, Bill Monroe & His Bluegrass Boys, Benny Carter, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, music from "Spellbound," and more

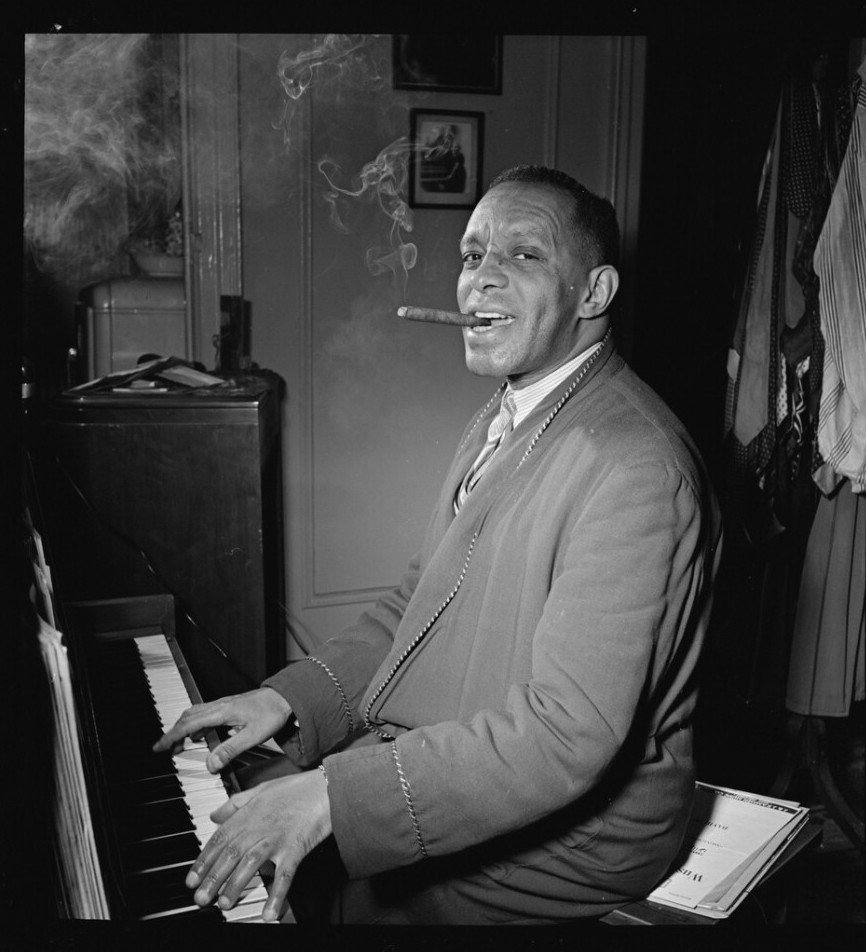

Featuring Coleman Hawkins, Bing Crosby, Art Tatum, songs from “Kiss Me Kate” and “The Philadelphia Story,” and more

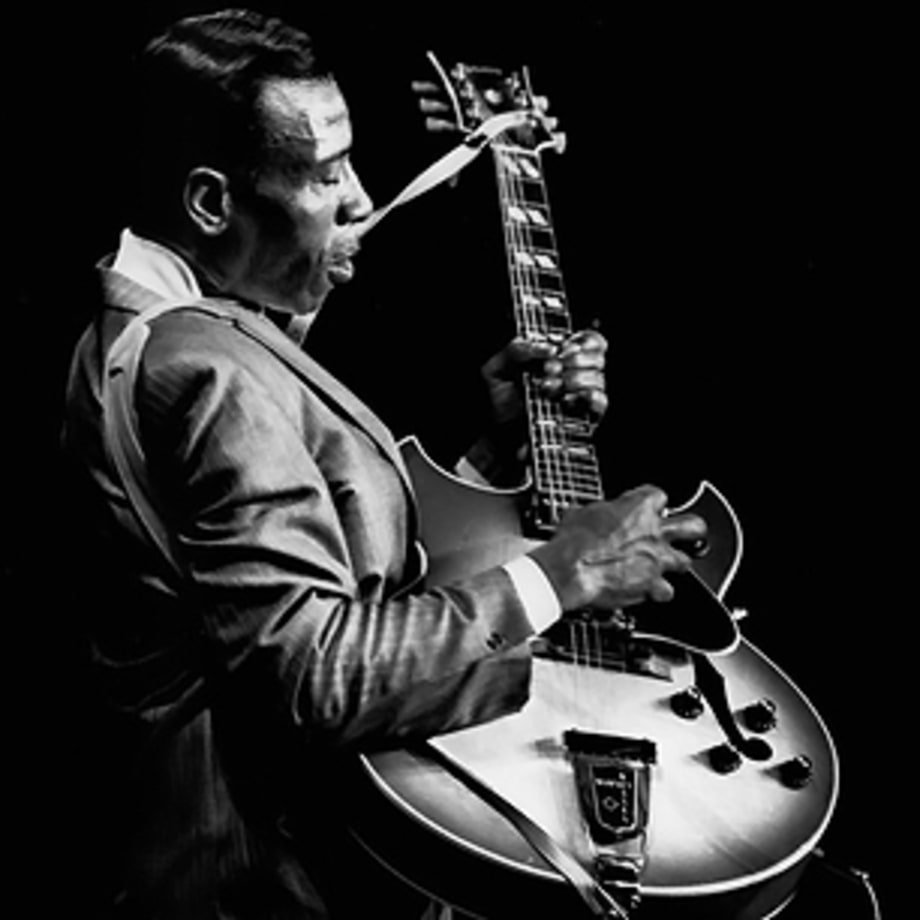

Featuring Jimmie Lunceford, Jimmie Rodgers, Ray Charles, Charlie Parker, Nat "King" Cole, and more

Featuring Dinah Washington, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, Muddy Waters, The Coon Creek Girls, and more

By Andy Miles

WHY A SHOW ABOUT THE tHIRTIES AND FORTIES?

Because the two decades produced a colossal advancement in American popular music, in both its production and dissemination, and the music is a joy to listen to.

When 1930 arrived, most American households had owned a radio for less than a decade; microphone technology had only recently become sufficiently advanced to capture studio and live ballroom performances; the industry standard 10-inch 78 RPM shellac record could hold just three minutes of sound per side; Billboard’s first pop record sales chart had not yet been published (that would come in 1936); and commercial sound cinema was in its infancy (the first “talkies” were released in 1926 and '27). And the era of the music megastar was only dawning. Singers Rudy Vallée and Bing Crosby — both of them born in the first years of the 20th century — supplanted the overwrought belt singing of aging stars like Al Jolson by using the microphone to deliver intimate performances in a style that would be dubbed, with some derision, crooning. By the time he was 30, Crosby was America’s greatest radio and recording star and was becoming a fixture in motion pictures, where his screen time quickly expanded beyond the singing cameo. Crosby didn’t simply have a nice voice and knack for delivering warm and witty performances (as a singer and actor); he had the benefit of performing at a time when the great American songbook, as it would come to be known, was — year by year, show by show, film by film — being written. All of the great men, and a few women, of American popular song were active and in their prime during the 1930s and/or 1940s, most prominently Richard Rodgers & Lorenz Hart, George & Ira Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Johnny Mercer, Harold Arlen, Hoagy Carmichael, Harry Warren, Oscar Hammerstein II, Jule Styne, Jimmy Van Heusen & Sammy Cahn, Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn, Arthur Schwartz & Howard Dietz, Alan Jay Lerner & Frederick Loewe, Betty Comden & Adolph Green, Kurt Weill, Vernon Duke, and Dorothy Fields.

Crosby wasn’t the only stage and screen singer to benefit from this prodigious roster of “Tin Pan Alley” talent. Having already become known for introducing Cole Porter and George & Ira Gershwin songs on the musical stage, Fred Astaire took his Broadway fame to Hollywood and introduced to movie audiences a long list of great standards: “A Fine Romance” (Kern & Fields), “A Foggy Day” (Gershwins), “Cheek To Cheek” (Berlin), “Isn’t This A Lovely Day” (Berlin), “Let’s Call The Whole Thing Off” (Gershwins), “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” (Berlin), “Nice Work If You Can Get It” (Gershwins), “One For My Baby” (Arlen & Mercer), “Pick Yourself Up” (Kern & Fields), “The Way You Look Tonight” (Kern & Fields), “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” (Gershwins), and many more. The 1936 Astaire musical “Swing Time,” starring Ginger Rogers as his elusive (and dancing) love interest, traded on a wildly popular movement of the mid-decade: swing music.

The Swing Era is thought by many to have begun August 21, 1935. On that Wednesday evening, Benny Goodman and his band kicked off a three-week engagement at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles, California. At the time, Goodman’s recording career was almost a decade old, some of his earliest sides having featured other future titans of the Swing Era: the trombonists Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey. In the year that preceded the Palomar gig, Goodman had become a popular band leader, recording a string of hit singles and securing far-flung exposure through national tours and radio broadcasts, notably NBC’s three-hour Saturday night “Let’s Dance” program. By then, Goodman had transformed the sound of his band by purchasing arrangements (“charts”) from the black bandleader Fletcher Henderson, whose band was one of the most swinging of the era. When the weekly broadcast put new demands on Goodman for fresh material, he hired Henderson, a bold step in mid-1930s America. Goodman had already made his mark on jazz integration by backing singer Billie Holiday on her first recordings, in 1933. In ’35, Goodman, with his new drummer, Gene Krupa, crossed the racial barrier again by joining Henderson’s band on stage in Chicago; that same year Goodman formed a trio that included the black pianist Teddy Wilson. Indeed, swing music represented an unusually integrated locus of American popular music, spawning as many legendary black band leaders (Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and Jimmie Lunceford among them) as white (Artie Shaw, Harry James, and the aforementioned Miller and Dorsey). By contrast, 1940s bebop (see below) was an almost exclusively black domain. Swing music also reached across the racial divide in terms of its following; for many white Americans, bands like Goodman’s was their introduction to jazz. When Goodman’s group brought those Fletcher Henderson charts to the Palomar, the fans went wild, and word of the conquest quickly spread.

As the 1940s began, band singers started to grab top billing; the greatest of them all was Frank Sinatra, whose career was launched with The Harry James Orchestra but caught fire with the more popular Tommy Dorsey Orchestra. Sinatra’s popularity — particularly among teenage “bobby-soxers” — motivated him to leave the band to begin a solo career. Though extracting himself from his contract with Dorsey proved onerous, the move paid off: Less than four months after leaving the band Sinatra began a solo engagement at New York’s Paramount Theatre that brought screaming bobby-soxers out in droves. It was December 30, 1942. Sinatra followed Benny Goodman on the Paramount bill. When radio star Jack Benny introduced Sinatra to the packed theater, the teenagers greeted the emaciated singer with a deafening roar. “What the hell is that?” Goodman famously asked Sinatra, who laughed and began his set. When Sinatra returned to the Paramount in October 1944, his appearance attracted so many fans — more than 30,000, it was reported — that the newspapers named it the Columbus Day Riot, reporting not only on the chaos outside the theater but mass fainting spells inside. (Some of those spells were no doubt produced by hunger and thirst: Many of the girls refused to give up their seats, hunkering down for multiple performances a day.) Sinatra’s recording career got off to a less auspicious start. When he signed with Columbia Records in the summer of ‘43, the American Federation of Musicians was on strike, effectively shutting down recording dates until the strike was resolved the following year.

The work stoppage also delayed the propagation of bebop (or “bop”), a new form of jazz that had taken root in New York City nightclubs — most famously Minton’s Playhouse — in the early ’40s. Little of its early development was documented on disc, meaning that when the strike ended and the first bop records were recorded and distributed, the harmonic complexity, rapid-fire soloing, and accelerated tempo of this new music created shockwaves in the jazz world. Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and saxophonist Charlie Parker, both of them products of 1930s swing bands, were the often rhapsodized, sometimes reviled progenitors of bop. Pianists Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell, trumpeters Clifford Brown and Miles Davis, saxophonists Sonny Stitt and Dexter Gordon, bassists Oscar Pettiford and Ray Brown, and drummers Max Roach and Art Blakey are likewise associated with the early evolution of bebop.

On the opposite side of the country, some of Hollywood’s greatest film composers, a few of them Jewish exiles from Nazi Germany, made their names during these decades. The European immigrants Franz Waxman (“Rebecca,” “The Philadelphia Story”), Miklós Rózsa (“Double Indemnity,” “The Lost Weekend”), Dimitri Tiomkin (“Mr. Smith Goes To Washington,” “Duel in the Sun”), Max Steiner (“Gone with the Wind,” “Casablanca”), and the American-born David Raskin (“Laura,” “Force of Evil”), Bernard Herrmann (“Citizen Kane,” “The Magnificent Ambersons”), Hugo Friedhofer (“The Best Years of Our Lives,” “Body and Soul”), and Alfred Newman (“Wuthering Heights,” “How Green Was My Valley”) formed the vanguard of orchestral composers during Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Far from either Hollywood or New York City, the South was the seedbed of two important forms of music that rarely, at that time, crossed the racial divide. Blues was music made by (and mostly for) African-Americans, while country was the preserve of white Southerners. The state of Mississippi, for example, produced blues legends Robert Johnson, Mississippi John Hurt, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B.B. King, all of whom were active during this period, though Waters and Wolf made their names in the thriving Chicago blues scene. The Grand Ole Opry helped make Nashville the center of the country music world, attracting icons like Jimmie Rodgers, Ernest Tubb, Roy Acuff, Hank Williams, Eddy Arnold, and Bill Monroe.

Female vocalists were in abundant supply during the 1930s and 1940s, leaving an indelible mark across the genres of big band swing and popular song (Ivie Anderson, Lena Horne, Maxine Sullivan, Mildred Bailey, Kate Smith, Jo Stafford, Helen Forrest, Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Margaret Whiting, The Andrews Sisters); jazz (Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday); blues (Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith); country (Patsy Montana, Cindy Walker); gospel (Mahalia Jackson, Sister Rosetta Tharpe); stage, screen and cabaret (Ethel Waters, Ethel Merman, Mary Martin, Édith Piaf, Judy Garland); and opera (Marian Anderson, Maria Callas).

By the late '1940s, record sales had soared to an all-time high, triggering technological advances in the industry. In 1948, Columbia Records introduced the 12-inch long-playing record, which, along with the recently developed 10-inch LP, ushered in the age of the album (which would fully blossom in the next decade; see “Giant Steps”). The LP was, for one thing, an ideal format for releasing original Broadway cast recordings, at a time when the Broadway musical was flourishing like it never had before, with many of the songwriters named above crafting cohesive “integrated” scores where the songs served to advance the narrative. Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II are the recognized pioneers of this form, Hammerstein having collaborated with Jerome Kern as early as 1927 on the integrated “Showboat,” Rodgers pushing the musical to new places with “On Your Toes” and “Pal Joey,” both in partnership with Lorenz Hart. In 1942, Rodgers and Hammerstein came together to create the watershed “book musical” “Oklahoma!” which opened the following March and ended its Broadway run more than five years later, a record at the time. Its original cast recording, released by Decca Records in 1945 on six 10-inch 78s, was the first of its kind, and sold a million copies*. “Carousel” and “South Pacific” followed, both shows preserved in the form of original cast recordings, which was true of other late ’40s Broadway hits like “Finian’s Rainbow,” “Kiss Me Kate,” and “Brigadoon.”

The LP also proved to be a further wedge between jazz and big band swing. By the late 1940s, jazz had largely vacated the ballrooms of the war years in favor of small clubs whose patrons preferred longer-drawn performances with increasingly daring improvisation — and sometimes tempos too fast to dance to. This preference was reflected in albums produced in the early years of the next decade, from veteran instrumentalists like Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge, bandleaders like Duke Ellington and Woody Herman, the new crop of players like Gerry Mulligan, Chet Baker, and Stan Getz, and the bebop trailblazers mentioned above. — Andy Miles, May 2023

Note and photo credits

* In 1949, “Oklahoma!” was issued for the first time on LP.

Pictured in the first gallery: Bing Crosby, Rodgers & Hart, Rogers & Astaire, Benny Goodman and Teddy Wilson, Frank Sinatra, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. Pictured in the second gallery: Thelonious Monk, Max Steiner, Robert Johnson, Hank Williams, Billie Holiday, Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

ALSO AVAILABLE: