KEEP ON PUSHING IS A MOTLEY AND MIND-EXPANDING EXPLORATION OF THE SIXTIES, WITH PLENTY OF AIR TIME GIVEN TO POP, SOUL, BRITISH INVASION, BLUES, BOSSA NOVA, BROADWAY, JAZZ, LOUNGE, FILM MUSIC, FOLK MUSIC, GARAGE ROCK, COUNTRY, AND MORE. ANDY MILES HOSTS.

WHY A SHOW ABOUT THE SIXTIES? SCROLL DOWN BELOW EPISODES AND FIND OUT.

EPISODES

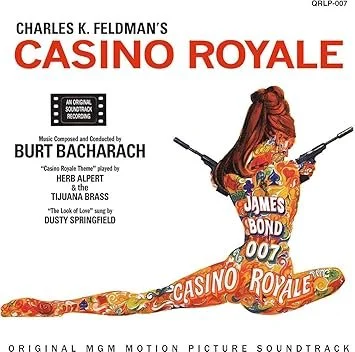

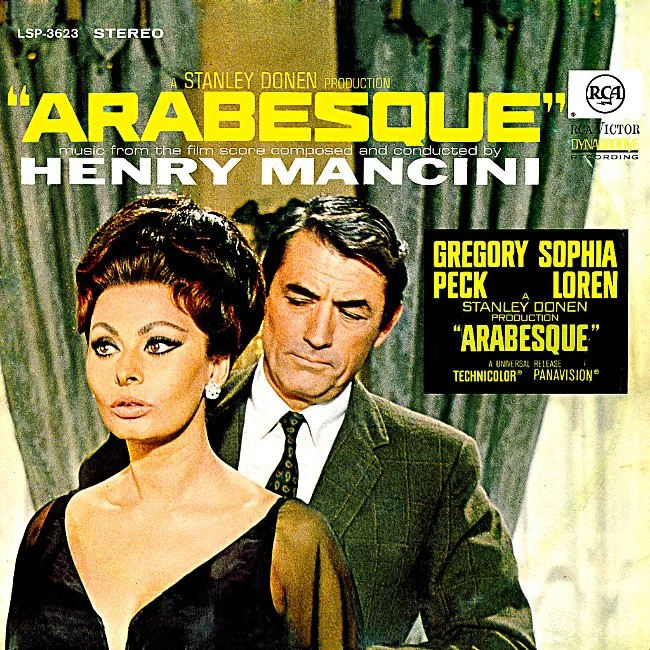

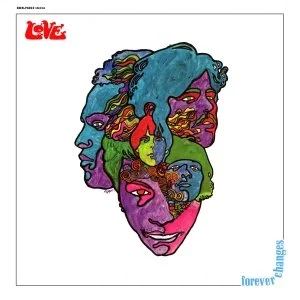

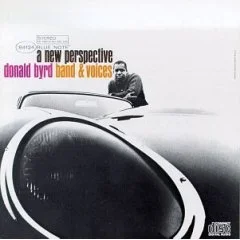

Featuring Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass, Bobbie Gentry, Johnny Cash, The Hollies, Donald Byrd, and more

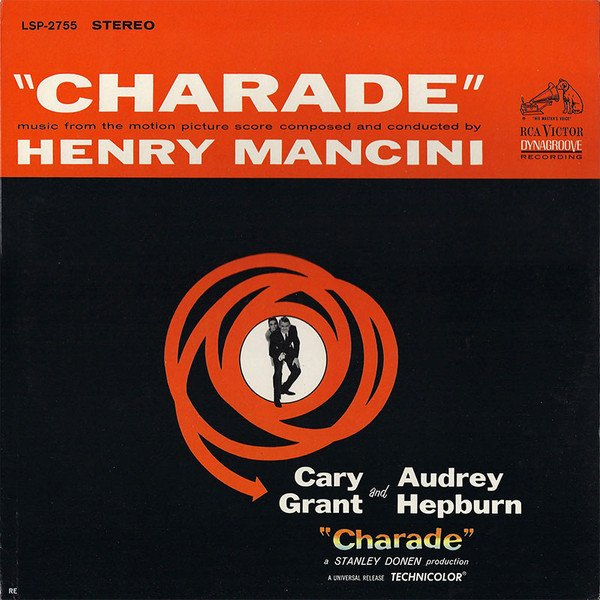

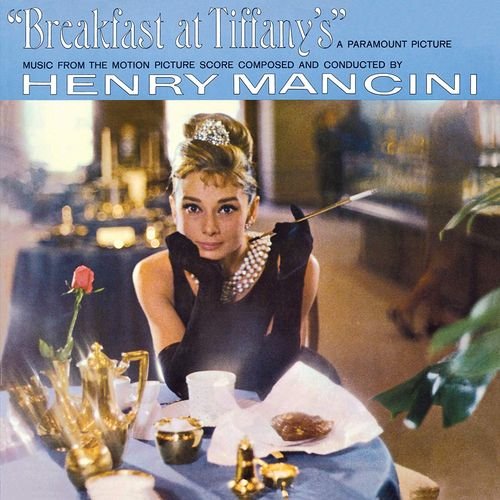

Featuring Henry Mancini & His Orchestra, Margo Guryan, June Carter Cash, Celia Cruz, Pharaoh Sanders, and more

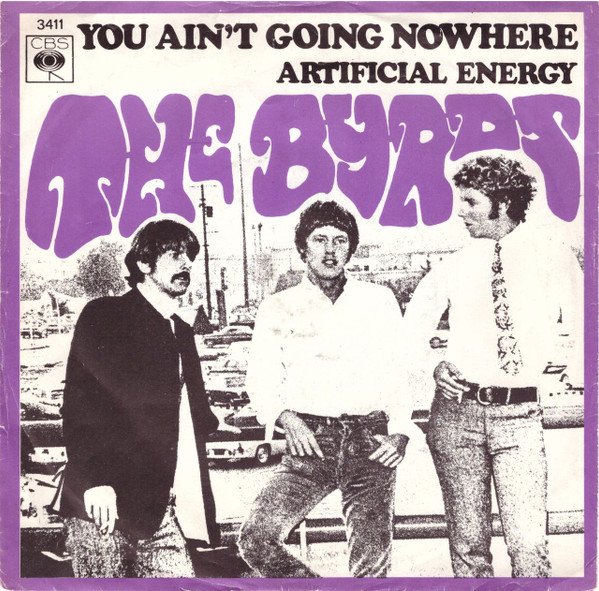

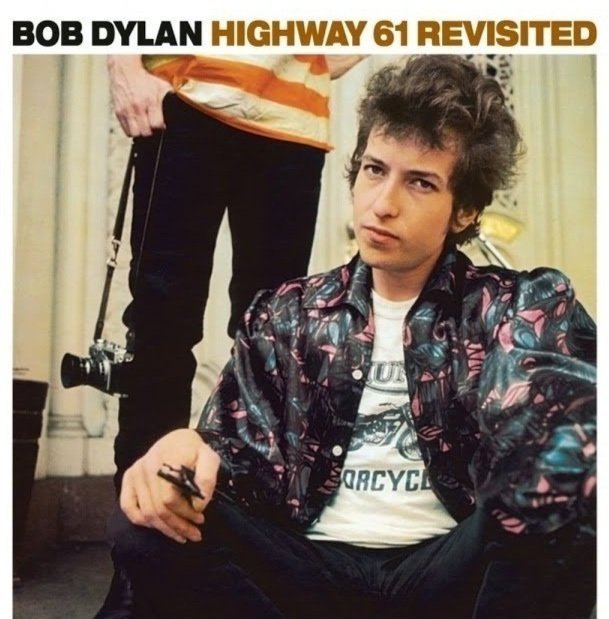

Featuring Chuck Berry, Gladys Knight & The Pips, Nancy Sinatra, Bob Dylan, The Byrds, and more

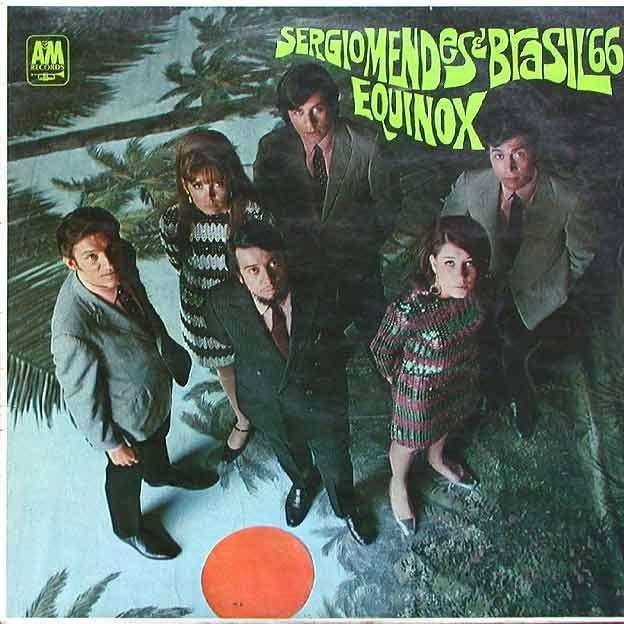

Featuring Nina Simone, The Moody Blues, Sérgio Mendes & Brasil ‘66, Frank Sinatra, The Rolling Stones, and more

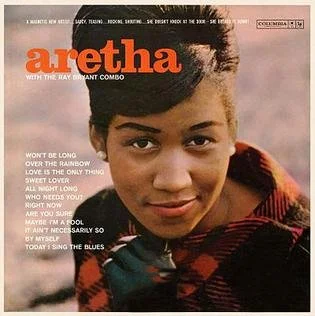

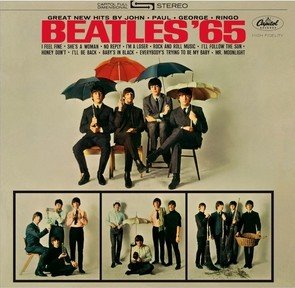

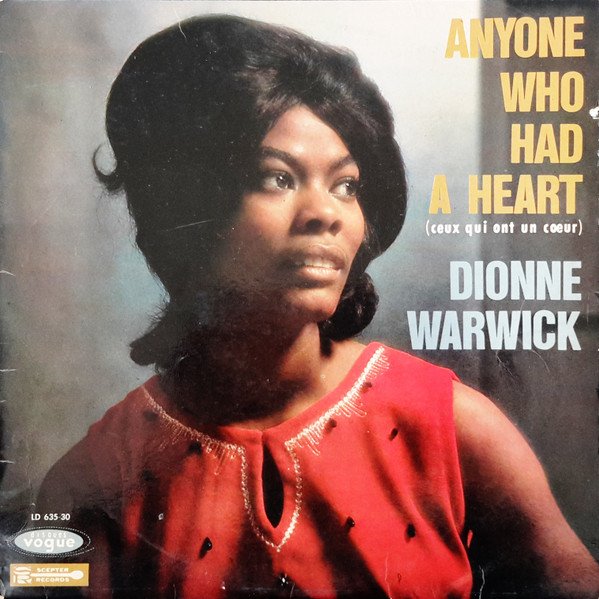

Featuring Oscar Peterson, The Staple Singers, The Beatles, Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick, and more

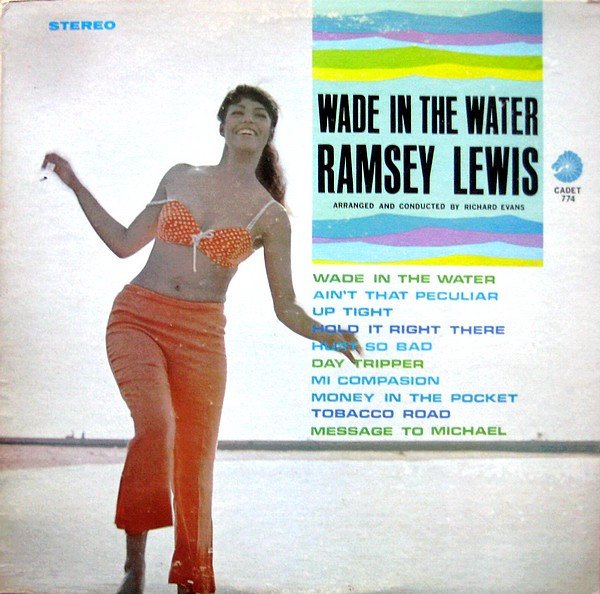

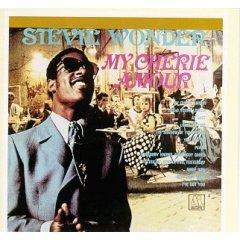

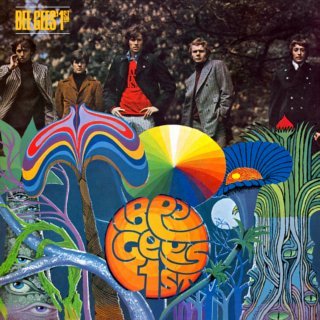

Featuring Buffalo Springfield, Ramsey Lewis, Stevie Wonder, The Bee Gees, Mel Tormé, and more

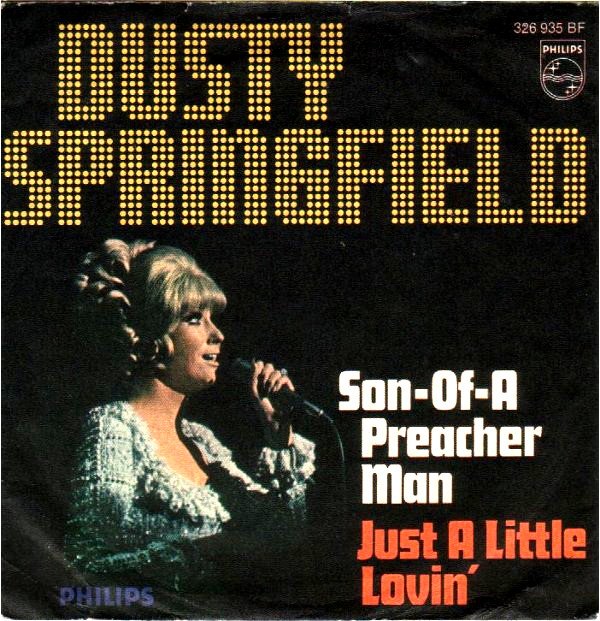

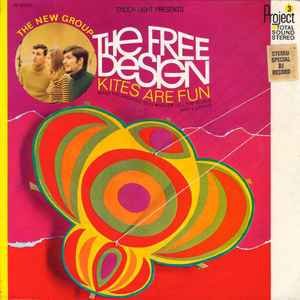

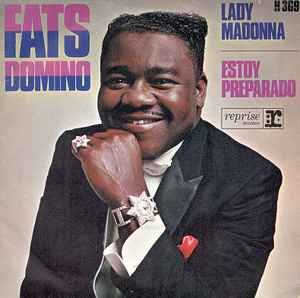

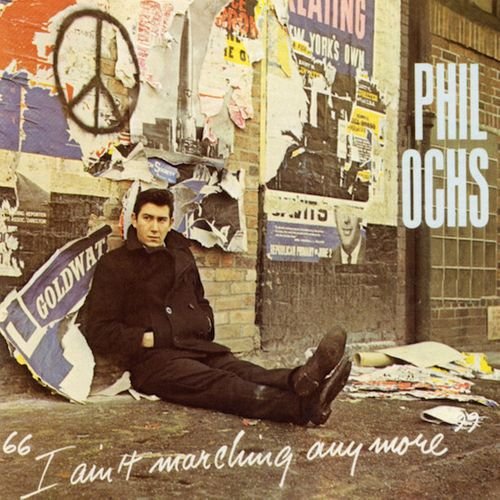

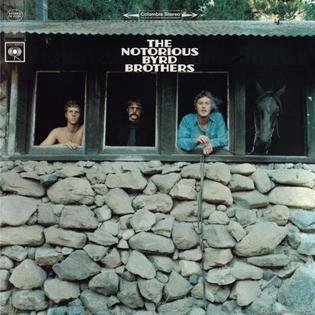

Featuring Buddy Guy, Roy Orbison, Dusty Springfield, Fats Domino, Phil Ochs, and more

Special Editions

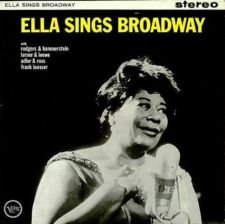

Featuring Charles Brown, The Beach Boys, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Otis Redding, and more

By Andy Miles

WHY A SHOW ABOUT THE SIXTIES?

Because it’s the watershed decade of 20th century popular music, whose creative flowering has influenced generations of musicians and music fans, across a wide swath of genres.

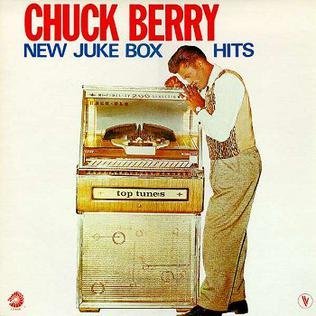

When the decade began, the music industry was in transition. Rock ‘n’ roll, so dominant in the last half of the prior decade, had endured several setbacks: a 1959 plane crash had taken the lives of Buddy Holly, J. P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson, and Ritchie Valens; in March 1960, Chuck Berry was sentenced to five years in prison for taking a 14-year-old waitress across state lines and having sex with her (he appealed the decision and subsequently served a year and a half in prison); Jerry Lee Lewis’s career was on the ropes following press revelations of his marriage to his 13-year-old cousin; Elvis Presley had been drafted into the Army (he was discharged in March 1960); and Little Richard had given up rock ‘n’ roll for preaching and making gospel records.

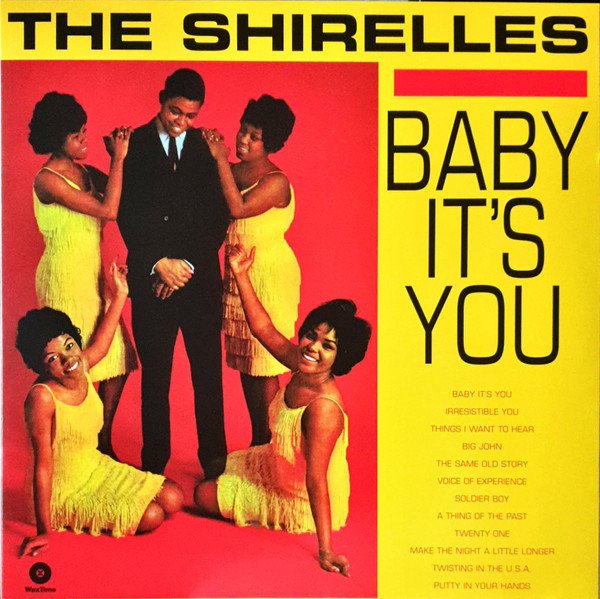

The professional songwriters who occupied offices in Manhattan’s Brill Building, near Times Square, would instead define early ‘60s pop music, creating — along with the producers and musicians — a majestic sound that replaced rockabilly-tinged rebellion with urbane, often Latinate testaments to the potency of teenage attraction and love (sometimes gone tragically wrong). Many of these songs appealed to listeners across America’s racial divide, finding crossover success on the pop and R&B charts. Brill Building hits frequently featured orchestral backing (and if Phil Spector was producing, the patented “wall of sound”*), with recording sessions populated by hungry young musicians whose names would, in some cases, have household familiarity by decade’s end; others toiled anonymously but were later lionized for their extensive, but uncredited, contributions to the decade’s great pop legacy. Songwriters Carole King, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka, and Sonny Bono would go on to forge successful careers as singers, while Burt Bacharach, Hal David, Gerry Goffin, Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, John Kander, Fred Ebb, and Marvin Hamlisch were familiar names — listed in songwriter-credit parentheses — on the labels of hit 45s; most of them went on to further fame composing for Broadway and Hollywood.

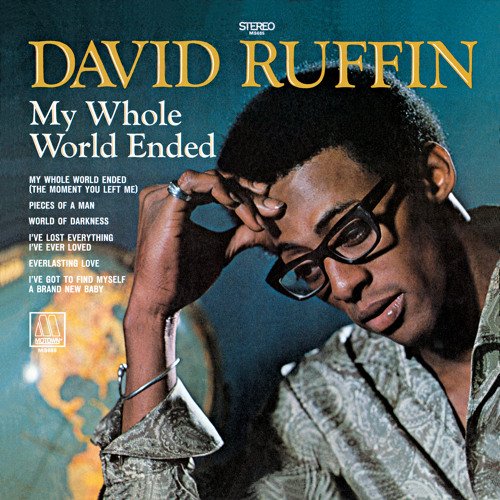

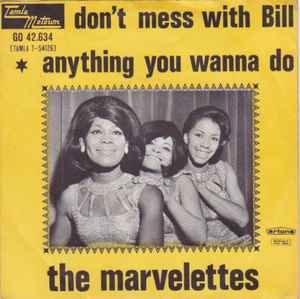

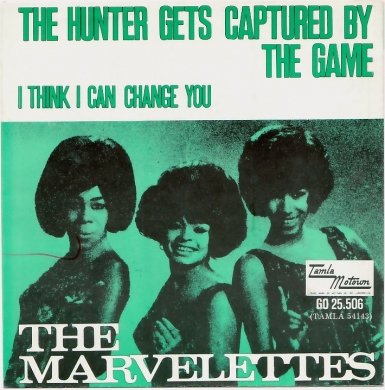

In Detroit, Motown Records was incorporated in the spring of 1960. That fall, they had their first smash record, The Miracles’ “Shop Around.” Hitsville USA, Motown’s Detroit headquarters, was exactly that, producing another 78 top 10 records during the decade — scores of them climbing to number one — for artists like Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, The Marvelettes, The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and Marvin Gaye.

The story of another famous soul singer — Memphis-born, Detroit-bred Aretha Franklin — attests to the continued demand, as the decade dawned, for the kind of torch singing that had made legends of Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dinah Washington in the previous two decades. When Franklin was signed to Columbia Records in 1960, her assigned repertoire covered similar stylistic ground: popular standards and show tunes, along with some gospel-infused R&B. Franklin wouldn’t find her truest voice — or lasting fame — until she joined Atlantic Records’ roster of soul artists, later in the decade. Meanwhile, Vaughan, Fitzgerald, and Washington (until her death in 1963), as well as younger singers like Nina Simone and Nancy Wilson, kept churning out popular albums and playing a national circuit of night clubs, theaters, casinos, and cabarets, as well as sometimes performing on television. The same was true for male singers of the American popular songbook, including Mel Tormé, Tony Bennett, Dean Martin, Vic Damone, Nat “King” Cole (until his death in 1965), and Frank Sinatra, who founded his own record label, Reprise Records, in 1960 and notched 14 top 40 hits in the decade, including a pair of number ones at the height of the ‘60s rock movement. Likewise, Broadway continued to be a fount of popular hits, with best-selling original cast recordings of long-running shows like “Bye Bye Birdie,” “Camelot,” “How To Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Funny Girl,” “Hello, Dolly!” “Man of La Mancha,” “On A Clear Day You Can See Forever,” “Cabaret,” “Sweet Charity,” “Hair,” and “Promises, Promises.” Production of film musicals declined sharply in the ‘60s, but screen adaptations of the ‘50s shows “Gypsy,” “West Side Story,” “My Fair Lady,” “The Music Man,” and “The Sound of Music,” as well as more contemporary fare like “Thoroughly Modern Millie” and Disney’s “Mary Poppins," played to huge audiences, as well as critical acclaim.

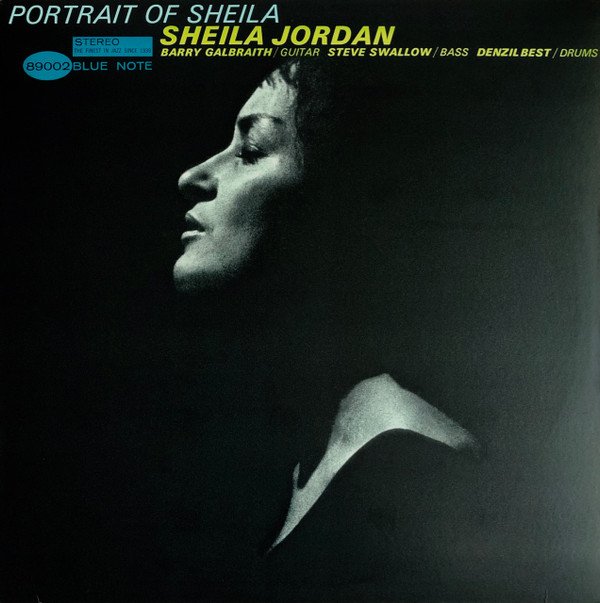

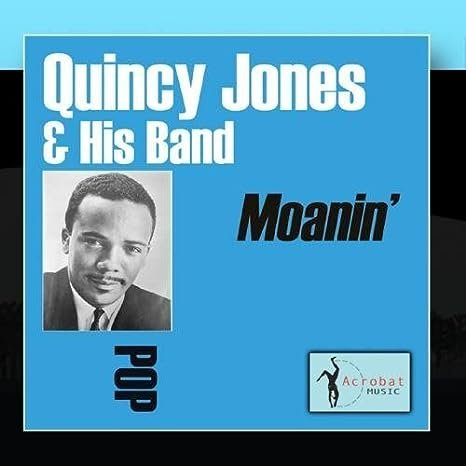

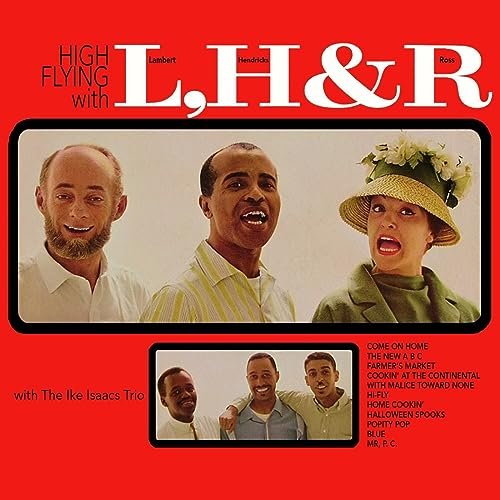

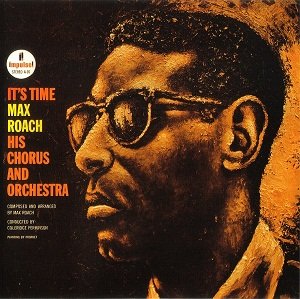

As jazz splintered into ever-more complex subgenres, audiences dwindled, but groundbreaking work came in the ’60s from established acts like John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Stan Getz (who became associated with the burgeoning bossa nova movement; see below), Cannonball Adderley, Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Jimmy Smith, Cal Tjader, Horace Silver, Sun Ra, and Ornette Coleman, as well as inventive players who first made their names in the ’60s: Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Archie Shepp, McCoy Tyner, Pharoah Sanders, Eric Dolphy, Herbie Mann, Alice Coltrane, Oliver Nelson, Wes Montgomery, and more.

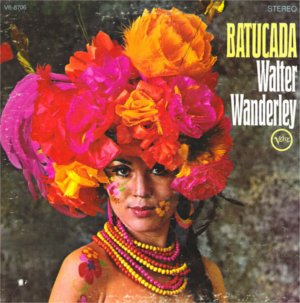

As noted above, jazz also formed an alliance with the bossa nova movement of the 1960s, its popularity catalyzed by Antônio Carlos Jobim, the great Brazilian songwriter and multi-instrumentalist whose work had first come to the attention of American audiences (and musicians) in the late ’50s but found mass appeal in the ’60s, particularly when “The Girl From Ipanema” became an international hit for Stan Getz with Brazilian vocalist Astrud Gilberto in 1964. Jazz instrumentalists and singers by the dozens recorded Jobim’s songs over the coming years, some of them in collaboration with Jobim as singer-guitarist (the Grammy-nominated “Francis Albert Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim” album, for instance). Jobim’s success, and the consequent uptick of American interest in Brazilian music, helped pave a path for Sérgio Mendes, whose band’s debut album, “Herb Alpert Presents Sérgio Mendes & Brasil '66” (produced by Alpert), included not only a pair of Jobim songs and the international hit “Mas que Nada” by the Brazilian Jorge Ben, but versions of Henry Mancini’s “Slow Hot Wind” and The Beatles’ “Day Tripper.” The latter was one of a string of popular Beatles covers the Mendes group recorded in the late 1960s, at a time when musicians across the stylistic spectrum were releasing covers of songs by the decade’s most important band.

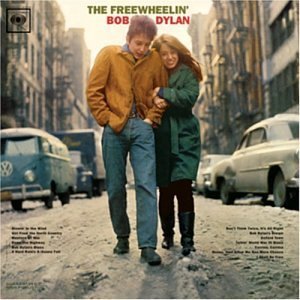

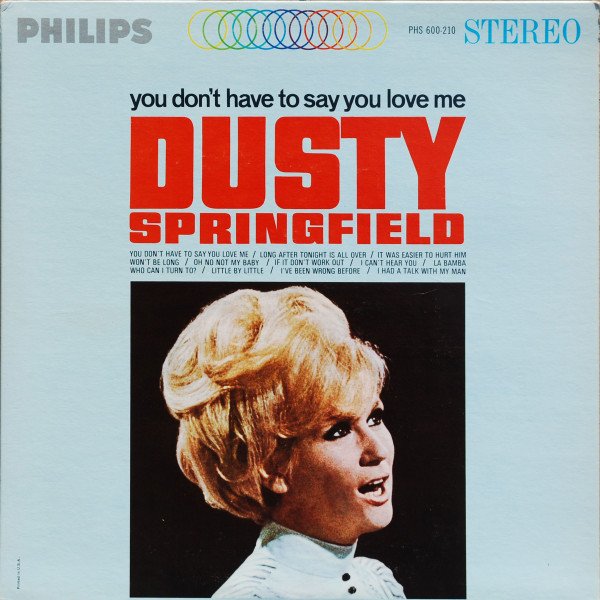

The Beatles story began in the latter part of the previous decade, when John Lennon and Paul McCartney met at a Liverpool church event where Lennon’s band The Quarrymen were playing. Not long after, they invited McCartney to join as rhythm guitarist. The band changed members and names, finally settling on The Beatles in 1960 (before the band’s final membership had been settled). After a now-legendary stint playing the Cavern Club in Hamburg, Germany, and honing their live-performance skills in their native Liverpool, The Beatles garnered enough attention to require the services of a manager, Brian Epstein; they then replaced drummer Pete Best with Ringo Starr, signed a recording contract with Parlophone Records, and recorded a minor British hit called “Love Me Do.” Between the song’s initial release in the United Kingdom and its subsequent release in the United States, in April 1964, The Beatles skyrocketed to international fame, arriving in America — barely more than two months after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy — to throngs of screaming, crying, sometimes fainting teenage girls, echoing (and far surpassing) the pubescent frenzy that followed Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley when they broke through in the prior two decades. When The Beatles played “The Ed Sullivan Show” two days after arriving in New York City, in February 1964, a record-breaking 73 million people tuned in to watch; within days, countless teenage bands had formed, many of them no doubt mimicking the group’s four-piece instrumentation** (two guitars, bass, and drums), energetic vocal harmonizing (with two singers at a mic), and preference for composing their own songs (though the early Beatles had a long list of covers in their live performance and recorded repertoire, many of the songs having Brill Building origins). Over the next couple years, hundreds of American “garage rock” bands would jostle for air time on radio and television, some of them achieving national (often one-time) chart success, others consigned to regional glory. Meanwhile, bands in Britain, who had in many cases beaten their American brethren to the punch, were booking American tours to capitalize on what had quickly become known as the British Invasion. The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Animals, Herman’s Hermits, and The Zombies led the first wave, but there was no shortage of contenders, many of them pocketing an American hit or two. Solo acts (Petula Clark, Dusty Springfield) and duos (Chad & Jeremy, Peter & Gordon) also came out of the British woodwork in the first wave. Many of the British bands — The Stones and The Animals, as well as Cream, The Yardbirds, The Who, and The Spencer Davis Group — were heavily influenced by American blues and R&B records that had been imported to Britain in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Other acts — The Moody Blues, Donovan, The Hollies — were just as inspired by American folk music, much of it coming out Greenwich Village cafés of the same time. By late 1964, The Beatles had fallen under the influence of Bob Dylan, by then the most famous of the New York City “folkies,” and for the next couple years filled their albums with a hit-producing mix of acoustic strumming and electric jangle.

Dylan had gotten himself a manager (Albert Grossman), signed a record contract (with Columbia), and put out a debut record (“Bob Dylan,” produced by John Hammond) around the same time as The Beatles had checked those boxes. He put his third album out the day after The Beatles made their first appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show”; its title track, “The Times They Are a-Changing,” proved as emblematic of the era as “Blowin’ in the Wind” had on his previous album (though neither charted in the United States). In early 1965 Dylan (in)famously went electric, turning off legions of his folk fans, many of whom booed his three-song electric set at the Newport Folk Festival that summer. Five days before the appearance, Dylan had released the electric-guitar-and-Hammond B2-suffused single “Like A Rolling Stone,” which became the highest charting single of his career. By then, the folk movement Dylan had been an influential part of had mostly had its moment, and his music became a greater influence on folk-adjacent rock bands like The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield.

The Rolling Stones had likewise made a decisive move away from their roots — in their case Chicago blues — releasing a series of era-defining singles (“Satisfaction,” “Get Off My Cloud,” Paint It Black,” “Let’s Spend the Night Together”), and in late 1967 followed the psychedelic lead of The Beach Boys (“Pet Sounds”) and The Beatles (“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band”) by releasing “Their Satanic Majesties Request,” to mixed reviews. Their foray into psychedelia was short-lived; a year later The Stones released the first in a run of decade-straddling classic rock albums that began with “Beggars Banquet” and ended with “Exile On Main Street” (1972). These albums reflected the hard-edged tumult of those years, as did decade-ending releases by The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Doors, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Led Zeppelin. Soul, funk and jazz acts — from The Temptations to James Brown to Miles Davis (who was heavily influenced by Sly & the Family Stone) — made a similar shift, leaving behind the smoother edges and meticulous grooming of the earlier eras they came up in.

Meanwhile, stars like Glen Campbell, Johnny Cash (sometimes in duet with his wife, June Carter Cash), Patsy Cline, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Loretta Lynn, Roger Miller, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Conway Twitty, Hank Williams Jr., and Tammy Wynette helped bring country ever closer to pop music’s mainstream.

It’s all here on “Keep On Pushing” (whose name comes from The Impressions’ song, released in 1964). — June 2023

Notes and photo credits:

* Spector was one to inject the above-referenced Latinate details.

** And for those who could find and afford them, the distinctive instruments themselves (Rickenbacker electric guitars, the Hoffman viola bass, the Ludwig oyster pearl drum shells).

Pictured in the first gallery: Private Elvis Presley; Brill Building songwriters Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil and Carole King; Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. outside Hitsville USA; a LIFE magazine photo of Frank Sinatra in 1965, the year he celebrated his 50th birthday; Nina Simone; Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock. Pictured in the second gallery: Brazilian singer Astrud Gilberto and American saxophonist Stan Getz; Sérgio Mendes and Brasil ‘66; The Beatles; Bob Dylan going electric; British singer Dusty Springfield; June Carter Cash and Johnny Cash in 1968.

ALSO AVAILABLE: