“The Madison Connection,” a cover story in two parts, published by Isthmus (Madison)

Madison is represented in virtually every idiom that compromises the arts and entertainment in 20th century America. Our fair — and sometimes unfair — city can claim, in one way or another, distinguished exponents of the radio and television arts; rock, blues, jazz and classical music; poetry, playwriting and prose; painting, printmaking, and architecture; theater and film.

As we begin this new century, Madison counts as residents many famous individuals.

Musically, there’s pianist-composer Ben Sidran, a versatile jazzman; drummer Clyde Stubblefield, a true legend of soul music; Roscoe Mitchell, reed player and composer; Richard Davis, professor of jazz and double-bass; Butch Vig, record producer and Garbage-man; and the Pro Arte String Quartet, a fixture here since 1938.

Author Kevin Henkes produces popular children’s books; Lorrie Moore writes splendid literature; Jacquelyn Mitchard is a best-selling novelist.

Artists Warrington Colescott and John Wilde have forged careers of international recognition from remote corners of our region for more than 50 years.

There’s public radio personality Michael Feldman. Even writer-director David Lynch has frequented Madison in recent years. And bluesman Luther Allison and Madison’s Chris Farley won’t soon be forgotten.

But what about those who came before them? Madison’s arts history is a decidedly rich one, with personalities that reflect our current times. From the unsung and the long forgotten to the overly exposed, the history of Madison and the arts touches on many threads that are the fabric of the 20th century.

Here, in two parts, are the stories of those personalities.

PART ONE

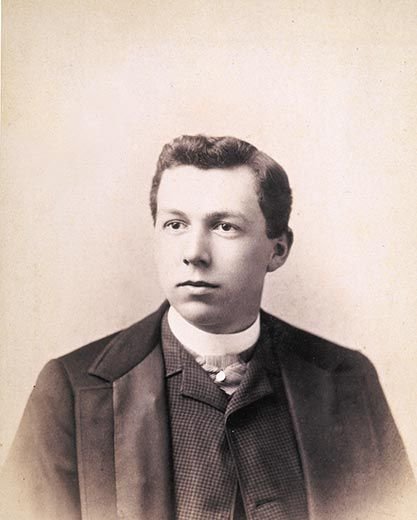

Frank Lloyd Wright is a big subject. This is a small article. Even such an apparently specific topic as Frank Lloyd Wright in Madison is the topic of a full-length book, Frank Lloyd Wright in Madison.

Wright had a history in Madison that was blustery and paradoxical, much like the architect himself.

Madison was the small 19th-century town where Wright spent formative years of his youth, living on Gorham St. while attending Madison High and the University of Wisconsin (where he is known to have received only C’s in parts of two school years).

Madison was also the setting for several Wright-designed structures — some of them seminal efforts — and the proposed setting of several more never executed.

And Madison was the site of several decades of strife and estrangement relating to his many unpaid debts, his use of the city’s platforms to launch haughty critiques of society and architecture, and his protracted campaign to erect a civic center on the site overlooking Lake Monona, where his posthumous convention center now stands.

But one Wright story has been largely neglected, or not recounted at all. In 1931, only a year before Wright would irrevocably remake himself with his apprentice camp at Taliesin and the designs for such architectural beacons as Fallingwater and the Johnson Wax buildings, Wright was a guest of the Experimental College at the University of Wisconsin.

The students invoked the “Ex College” rule that only residents of the host house could be in on the talk. Several hours late, Wright finally pulled up in his Taos-red L29 Cord Cabriolet; he blustered into the den of Richardson house, declaring, “This is an awful place and I refuse to talk here,” then directed his undergraduate hosts to rearrange the room and start a fire.

In the two-hour talk that followed, Wright expounded not on architecture but on the meaning of Taoism. As he parted, he left his spellbound students a simple credo: “Don’t always accept things as you find them.”

Geographically, Georgia O'Keeffe distanced herself long ago from her Wisconsin birthplace. It was understandable. What was more difficult to understand — or even forgive, apparently — was the symbolic distance she placed between herself and her hometown, Middleton, in 1976. Twenty-four years and the artist’s death in 1986 have presumably blunted the affront to civic pride that was delivered by her refusal to either accept an invitation to come “home” to Middleton for the dedication of a park in her name or to send the town one of her paintings. (A petition was quickly circulated and the park’s name was changed).

These requests may have seemed as far-fetched in 1976 as they do now. O'Keeffe’s reputation as a major American artist was assured and her appeals for privacy well publicized. And Middleton — the state of Wisconsin, for that matter — had shown little interest in her until then. It would be another eight years before the state opened its first major retrospective of O'Keefe’s art, a 33-painting exhibit at the Madison Art Center that drew 43,000 people and doubled art center membership.

O'Keeffe moved to Madison at the age of 13 to attend the Sacred Heart Academy, almost a century ago. At Sacred Heart (later Edgewood College), she received art instruction in a studio overlooking Lake Wingra. The next year, while living with her brother and her aunt in a two-story house on Spaight Street, she was enrolled at Madison High (later Central High). There her training as an artist continued, significantly with an encounter she later recalled as “the first time my attention was called to the outline and color of any growing thing with the idea of drawing or painting it.” The growing thing was a flower.

For many, the lure to move beyond Madison proved too powerful to contain them within these city limits — or the boundaries of this state. For William Ellery Leonard, poet and pedagogue, the choice was not his to make.

In a period covering more than 30 years, Leonard, the victim of a distance phobia, rarely ventured beyond six blocks from his campus apartment. The Locomotive God was the name he gave his tenacious demon (and his autobiography), the painful manifestation of a long-repressed episode from Leonard’s early adolescence involving a passenger train.

That his inflated retelling of the incident borders on the delirious (the train becomes a thing of “infinite menace … to swallow me down, to eat me alive … Hideously hostile … huge … God … Death”) is beside the point. Actually, it is the point. Leonard’s saga was so unflinching in its detail that the book became the subject of psychiatric analysis, much as Leonard himself had been.

Leonard left other legacies as well. His sonnet sequence “Two Lives,” with its many parochial references, was conferred standing as the longest sonnet in American poetry (over 3,000 lines) and won the adulation of a local critic who called the work “the most monumental piece in American poetry.”

Yet by 1961 Herb Jacobs, in another Madison daily, could portray Leonard as “being completely unknown to many students,” a condition that, despite a smattering of locally published remembrances since, has only been compounded by 39 years.

Two of Ellery’s students, lyric poets Horace Gregory and Marya Zaturenska, never met at the University of Wisconsin. They met instead in New York City, introduced in the summer of 1925 by another poet and Badger alumnus, Kenneth Fearing [see next entry], who had worked with both young poets at the “Lit,” the Wisconsin Literary Magazine.

Gregory, a Milwaukee native, left Madison only months before Zaturenska came here in 1923 as a Zona Gale scholar and a student in the library school. They married and lived together in New York, where Gregory had come after graduation and taught for many years at Sarah Lawrence College.

Individually, they each published eight volumes of verse, at roughly corresponding intervals, and were accorded the highest literary honors (Zaturenska, the Pulitzer Prize; Gregory, poetry’s highest honor, the Bollingen Prize). Together they collaborated on several books, including A History of American Poetry, 1900-40 and a poetry anthology for young readers.

Poet and novelist Kenneth Fearing’s time here, largely forgotten — as much as his literary output has been — was marked by a precipitous rise and fall. The “rise” saw him named editor-in-chief, a newly established position at the Lit, after serving as associate editor for only one semester. The “fall” came in a bitter sequence of events that led to his ousting just six months later. Fearing revamped the student monthly, waging war on “stupidity” without “succumbing to mere literary sogginess,” and incurring serious debt in the cause. In March, despite a circulation drive that produced record sales, Fearing was discharged when a committee of deans and faculty advisers deemed the cheeky editor-in-chief “intolerably misanthropic, sour and biting.”

Those qualities would not prove to be obstacles in Fearing’s path after graduation. Writing in the so-called “living idiom” he published six collections of poetry and several novels, including the suspense drama The Big Clock, which was produced as an effective 1940s film noir.

Poet Delmore Schwartz lived the kind of turbulent life that makes compelling fiction. (Saul Bellow based the title character in his novel Humoldt’s Gift on Schwartz.) Considered the most promising poet of his generation before he was 25, Schwartz spent his next 25 years desperately trying to realize that promise. He published poems, plays, criticism and essays. He was an associate professor of English at Harvard University, an editor of poetry at the New Republic. At 46 he was the youngest poet to win the coveted Bollingen Prize.

Then in 1966 he resigned from the English department at Syracuse University and faded from sight, living in a hotel in Midtown Manhattan. Six months later he was dead, the victim of a heart attack.

Maurice Zolotow, a classmate of Schwartz at the University of Wisconsin and himself an author, remembered those last years as “crazy, demonic, right out of Dostoevsky.” In their university days, Schwartz and Zolotow frequented Paratores, a local speakeasy, and moved in a circle of boisterous, would-be intellectuals. Schwartz lived in Adams Hall in a room that overlooked Lake Mendota. “How beautifully stars shine in the forehead of each Wisconsin dusk” he wrote.

After a year of mixed success as a student, Schwartz skipped his last exam and boarded a bus back home to New York.

“Death Closed Brilliant Life of Zona Gale” the Milwaukee Journal headline read in December 1938. Gale’s death was reported on the front pages of newspapers around the state. Yet, more than 60 years after her death, Zona Gale’s life inspires little attention. The subject of only one significant biography, published in 1940, study of Gale’s life and work has scarcely been shouldered by those in scholarly communities, and the sizable body of fiction she produced has slipped quietly into disuse.

Gale was born in Portage in 1874, coming to the University of Wisconsin 17 years later. Having already published her poetry in the Portage Democrat, she was seduced by the prospect of publishing monthly in the campus literary journal, the Aegis. There she placed wistful works of poetry and prose for several years, ultimately becoming the magazine’s general editor. Her work then, much as her earliest commercial output, offered little indication of the tenor and caliber her later novels would acquire.

After 1912 she became increasingly political, having fully absorbed the tenets of LaFollette Progressivism, and began to produce the finest work of her career. She turned her novel Miss Lulu Bett into a 1921 Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, and reaped the success of her other novels and plays.

On campus, she continued to be active, appearing before campus groups, acting as faculty supervisor to the Wisconsin Literary Magazine, and serving as a university regent for six years.

Gale’s greatest legacy might have been as a patron of the literary arts. Unfortunately, the scholarships presented in her name never produced any truly meaningful result. In fact, one of the recipients, Eric Waldron, a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, reportedly squandered the stipend, as well as that of a Guggenheim fellowship, and never published in America again (he did not come to Madison). Another beneficiary of the fund, author Anzia Yezierska, suffered a similar fate.

In 1928, Yezierska’s career as an author, flourishing only two years before, was beginning its long eclipse. A Russian immigrant whose schooling was subsidized by wages earned in sweatshops and scullery on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Yezierska had emerged by 1922, in the words of the New York Tribune, “as romantic a figure as contemporary American literature affords.”

In only three years she had parlayed an extraordinary breakthrough as winner of the best short story of 1919 into success and tabloid notoriety as the author of two autobiographical novels (both adapted to the screen) and a salaried Hollywood scenarist.

Her 1925 novel, Bread Givers, relating her own story as the daughter of an oppressive Talmudic scholar-father, would become her ranking achievement. But the failure of her next work, Arrogant Beggar, precipitated a steady downward mobility that placed her at the doorstep of her friend Zona Gale, who presented Yezierska a Gale Scholarship in 1928.

Shortly after her arrival here, the authoress expressed harmony with her new surroundings. She called Madison her “first contact with real America, because New York is not America.” And she extolled the “wide open spaces” and “silent black nights with the bright stars.”

But the author’s short time here brought only further disappointment. She called the university a “petrified forest of dead knowledge,” and grappled with her many insecurities as an author. The book she was ostensibly at work on did not materialize. In fact, it would be four years until any new book of hers materialized, and that was her last for almost 20 years. She died in 1970 in relative obscurity.

In her four semesters at the UW, Eudora Welty, who earned her B.A. in 1929, scarcely asserted herself as a writer of prose or poetry. Her sole foray into the literary realm was a poem published late in her junior year by the Wisconsin Literary Magazine.

Having transferred here from Mississippi State College for Women, where she helped found that college’s first literary publication, Welty expected to leave Madison an artist. But first she discovered that she lacked the requisite artistic gifts, and then she discovered Yeats in long visits to the Celtic division of the campus library.

Still, she left Madison without any obvious literary intentions, continuing her studies at the Columbia Graduate School of Business. By 1936 she was back in her home town of Jackson, Miss., publishing her first short story, “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” and establishing a long writing career that won her the attentions of both the scholarly community and a large reading public.

The range of her literary output includes short stories, novels, poetry, book reviews, essays, and photographic collections. Her novel, The Optimist’s Daughter, set in the South like most of her work, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973.

Marjorie Kinnan, whose lasting fame was clinched with the 1938 publication of The Yearling, also published poetry in theLit, and far more regularly. At the Lit, Kinnan wrote buoyant and lively stories and verse, also contributing book reviews and editorials (once in the same issue).

But that was only one activity that occupied Kinnan during four vigorous years at the university. In fact, her various literary endeavors (as an associate editor of the Wisconsin Literary Magaazine, the Awk, and the Badger yearbook) are nearly obscured by her many dramatic pursuits. A member of the women’s dramatic club Red Domino, she participated in Union Vodvils, winning first prize for her own pantomimic comedy “Into the Nowhere.” Her starring role in the junior class play won her the praise of the Daily Cardinal, which found “the amateur element … entirely lacking in her interpretation.”

Upon graduation, the Washington, D.C.-native moved around the country with her husband, Charles Rawlings, whom she met at the Lit. They finally settled in Cross Creek, a remote 72-acre orange grove which they purchased in central Florida. The scrub-pine backwoods of the region and the “crackers” who inhabited it would become the colorful inhabitants of her many short stories and novels, which include Golden Apples, Cross Creek and The Yearling.

For Thornton Wilder, Madison was a sleepy, turn-of-the-century burg of 18,000 that would help form the rustic Americana embodied by his greatest success, Our Town. In creating the play’s fictitious setting, Wilder drew upon a small New Hampshire town where he had spent summer retreats. But as his biographer notes, Madison was the first of three “our towns” in Wilder’s youth — along with Berkeley, CA and New Haven, CN.

Born in Madison in 1897, Wilder lived the first nine years of his life here, his time shared between family residences on Langdon and Gilman Streets and a summer cottage, “Wilderness,” in Maple Bluff. His father, Amos Wilder, came to Madison with his new wife in 1894 to begin a tenure as editor of the Wisconsin State Journal. The elder Wilder was a passionate social crusader and used the newspaper, which he assumed a controlling interest of in 1901, as a platform to convey his convictions. Thornton, the second of four Wilder children born in Madison, accompanied his father in trips to the offices of the State Journal, then located on East Washington Ave.

Away from Madison since 1906 when his father was appointed consul general to Hong Kong, Wilder came home to Madison at least twice. He first returned in 1929 (a Pulitzer Prize winner and literary star), and again in 1940 for centennial services at First Congregational Church, which Wilder had attended as a boy.

PART TWO

It was 1924 when University of Wisconsin graduate Frederick Bickel deemed the “k” in his first name expendable and gave himself a more euphonious surname, adapting his mother’s maiden name, Marcher, for the cause. By then Fred Bickel was an established extra on stage and screen.

When Frederic March returned to Madison in December 1927, his appearance at the Parkway Theater was much heralded. Having finally established his name on the theatrical stage, March was in Hollywood just a few months later signing a five-year contract with Paramount, the studio that catapulted him to national fame in 1932 with his Oscar®winning performances as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Born in Racine, Fred Bickel came to the UW, a finance major, in 1914. “College,” he recalled, “was no more eventful than it usually is. You must be wondering where the highlights of this classic tale come in. I’m wondering, too!”

The highlights, of course, were many. Bickel was active in athletics, politics (as senior class president), and dramatics. As an entertainer, Bickel was a sort of a Vaudevillian song-and-dancer, affiliating himself with campus Thespian groups Edwin Booth and Haresfoot.

When he died in 1975, March was remembered for his many screen credits, credits that include Inherit the Wind and The Best Years of Our Lives, a film that earned him a second Oscar®. His Broadway portrayal of the aging actor James Tyrone in Eugene O'Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night also netted March a Tony® Award.

With dramatic experience at three previous schools, Don Ameche, a native of Kenosha, was no theatrical novice when he came to Madison in 1928 as a first-year law student. Still, it took the combined conquests of his role in the university production The Devil’s Disciple and as co-star in the second semester triumph Liliom to finally propel him away from the law and toward theatrics of another sort.

A dapper young man of 21, Ameche left the university after a year, swiftly landing parts on Broadway, in radio, and later in films and television. He is remembered for countless film credits from the ‘30s and '40s (Moon Over Miami, Heaven Can Wait), and more recently, for his Oscar®-winning role in Cocoon.

And now a trivia question: In a famous scene in the 1955 film The Seven Year Itch Marilyn Monroe stands over a subway grill and lets a blast of air inflate her white dress. Who was her companion, standing by with smiling admiration?

If you answered Tom Ewell you know your film history. If you answered Yewell Tompkins, you should be writing this article!

It was in 1931 that Tom Ewell, known then as Yewell Tompkins, left Madison for Manhattan to make a career for himself on Broadway. Unfortunately, his professional acting career would play out much as his amateur acting career in Madison had — only in Madison he didn’t get to star opposite Marilyn Monroe in a certified Hollywood film classic.

Once called a “casting enigma, ” Tompkins was never possessed of the handsome looks that win actors handsome leading roles. More than 20 failures had been counted by 1952, the year The Seven Year Itch opened, with Ewell as its star, on Broadway. But by then the actor was counting performances of The Seven Year Itch, of which there would be more than a thousand.

Ewell, who participated in 730 of those performances and collected a Tony® Award for his work, was prescient when he said, rather pessimistically: “I’ve been waiting 43 years for a part like this. I’ll never have a good one again.”

Chris Farley had one more thing to do before settling into a regular nine-to-five life. He wanted to try a career as a performer. For those who knew Farley at Edgewood High School, news of that ambition might have come as a surprise. In high school, Farley, a self-confessed “nun’s nightmare,” was a jock, playing on the football team. He also played the part of class clown (he was reportedly given a semester’s sentence at an Indiana boarding school after running naked in the halls at Edgewood and knocking a nun over). But it wasn’t until he went away to college, to Marquette University, that he dabbled in theater. Even then, his career path might have seemed unclear — he played only dramatic roles.

Graduating in 1986, Farley came home to Madison to work for Scotch Oil Co., the family business started by his grandfather. He also began performing with the Ark Improvisational Theater. A year was all he needed. He moved to Chicago and quickly impressed Del Close, the major figure in Chicago improvisational comedy. Close coached Farley at Improv Olympic, the school and performance space Close co-founded on Chicago’s North Side, and directed him at Second City.

For two years Farley worked tirelessly, six nights a week, two shows a night with Second City, quickly rising to Main Stage exposure. That exposure led to his discovery by a “Saturday Night Live” casting agent and Farley was signed to the show only weeks before its season premier in 1990.

In Farley’s steady climb to stardom, creating memorable SNL caricatures and starring in a string of crude Hollywood comedies, stories of his excessive lifestyle quickly circulated. In Madison, very real concerns for his well-being were tempered only briefly by assurances given by Farley to Doug Moe in a 1994 Madison Magazine feature story. “I was on live national television at 26 [and] I was very scared,” Farley said. “Maybe I was a little wild. This kind of atmosphere cradles that wilderness. But I’ve calmed down. I found out it’s not tolerated. … People who get out of control fall by the wayside. I didn’t want that to happen to me.”

Repeatedly serving suspensions during his SNL tenure in order to “clean up,” Farley’s last few years, away from the show, were fraught with those same bouts with excess. “Chris Farley on the Edge of Disaster” came the prophetic judgment ofUs magazine in 1997. In December of that year Farley was found in his pajama bottoms, dead on the floor of his 60th floor Chicago apartment, a 33-year-old casualty of a drug overdose.

Eighty years old, the German-born Uta Hagen [pronounced OO-tah HAH-gen] has been at it, starring on and off Broadway and operating a famous acting studio for the better half of a century.

She was Blanche in A Street Car Named Desire, Georgie in The Country Girl, and Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? — demanding roles that won her screen counterparts Best Actress Oscars (Hagen herself didn’t appear in a Hollywood film until 1972).

And the New York studio founded by her second husband, the late Herbert Berghof, has long been the setting for perhaps her greatest role, as teacher of a cast of thousands — young actors with names now more famous than her own: Jack Lemon, Jason Robards, Geraldine Page, Lily Tomlin, Matthew Broderick, etc.

Something of a teenage prodigy, Hagen first cultivated her own dramatic skills behind the footlights of Bascom Theater. It was there that she appeared in various productions of the long-defunct University of Wisconsin High School, and in summer stock productions of the Wisconsin Players. One of those performances attracted the praise of one local theater critic who declared Hagen, then a high school senior, “a remarkable talent … [who] should some day reach the heights.”

Hagen presumably couldn’t wait that long. Leaving Madison after only a semester at the UW, she quickly ensconced herself on stages large and small, appearing in almost a dozen shows before she was 20 years old. Only five years later she would come home to Madison, a star, with her husband-actor Jose Ferrer and Paul Robeson, to render two sold-out performances of Othello, their wonderful stage success imported from Broadway. “A storybook homecoming,” reported the Capital Times on its front page of December 5, 1944. “One of the major events in the annals of Madison’s theatrical history.”

Last year Hagen accepted the Tony® Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Once called the “Wisconsin Marilyn Monroe,” actress Gena Rowlands’ cool, blonde beauty is not easily overlooked. Her UW classmates, apparently, couldn’t see much else. In three years at the university, Rowlands, a native of Cambria born in Madison (Cambria didn’t have a hospital), occupied the campus stage more often as a debutante than as an actress.

But Rowlands didn’t let the relative dearth of acting parts discourage her. She knew she wanted to be an actress and dropped out of college her junior year to become one.

Leaving Madison, she may not have known what kind of actress she would become. Initially, she followed a conventional route, working up through stock to off-Broadway, Broadway, television and films. But the actress Rowlands became was uncompromising in her fidelity to purposeful work, eschewing inferior roles even if it meant not working for several years — which it did.

Hesitant at first to work with her husband, writer-director John Cassavetes, ultimately Rowlands swore off all other films except the films he wrote for her — films that include Faces, A Woman Under the Influence and Opening Night. Since Cassavetes’ death in 1989, Rowlands has continued to take on challenging roles (Night on Earth) while also appearing in more mainstream fare (Playing By Heart).

John Steuart Curry’s gifts as an artist were always in question. He questioned them, critics questioned them, even politicians questioned them. The most conspicuous evidence of Curry’s craft may be as a muralist; his works as a WPA artist during the Depression and the lingering mural commissions he received until his death in 1944, are documented in great halls of higher learning and civic discourse, from state capitols (including our own) to our nation’s Capitol.

When he died of a heart attack in 1946, a retrospective exhibit of his art then being prepared at the Milwaukee Art Institute became a moving tribute to the late artist. Fifty-two years later, an exhibit of Curry’s drawings and paintings given by the Elvehjem Museum of Art resuscitated interest in the painter and the regionalist movement in which he worked.

He came to Madison in 1936 as artist-in-residence in the School of Agriculture, the first such appointment in the nation. Midwestern regionalism was at its height as an artistic style, and the major exponents of the form — Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Curry — enjoyed celebrity status. Curry himself was the subject of a feature article in the first issue of Lifemagazine.

Curry lived in Madison on a $4,000-a-year salary, painting in a campus studio specially built for him. His professional obligations were exclusively as an artist, relieving him of teaching assignments or even public appearances. Despite his fame, Curry chose to live fairly anonymously, committing himself full time to painting the provincial, agrarian themes that characterize nearly all of his work.

The New York Herald Tribune once called Aaron Bohrod, Curry’s successor as artist-in-residence, “a painter of such incredible skill as to leave one breathless.” It was a negative review. Bohrod was accustomed to detecting such duplicity in his plaudits, as mention of his technical command often served as terse preludes to critical aggression.

For 25 years he served the university, perfecting his “fool-the-eye” technique, a technique that fooled so many eyes that a “Do Not Touch” sign was often affixed to the gallery walls displaying his work.

For a time, Madison had two world-class concert pianists in its realm. Gunnar Johansen and Paul Badura-Skoda, artists-in-residence at the University of Wisconsin, made frequent campus appearances during their time here, enriching the local classical music-loving community immeasurably. But the pianists left markedly different legacies, both in Madison and in the larger thrust of their careers.

Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, Johansen came to the UW in 1939 after establishing himself with weekly radio recitals over NBC and an extensive tour schedule. In Madison he broadened his exposure with the resumption of radio broadcasts in 1945 — this time on radio station WHA, where his performances were recorded and distributed nationally over a tape network. It was there that he began performing the complete works of the composers he most cherished: Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Chopin, and finally, in 1951, Bach. From his home in Twin Springs, north of Blue Mounds, Johansen began recording the Bach cycle for distribution on his own Direct Artist record label, a mail-order subscription service.

Thus, a cottage industry had been fashioned from a cottage in the Wisconsin woods, where the owner chopped wood and practiced up to 10 hours a day on a collection of period keyboard instruments.

Johansen, once termed a “titanic virtuoso,” was content to resist the spotlight and live out his days in Wisconsin, quietly composing more than 500 piano sonatas and producing a 51-record series of Liszt recordings before he died in 1991.

For Austrian-born Paul Badura-Skoda, Madison rates no more than a footnote in a career that began more than 50 years ago and has carried him to every major concert hall in the world. Given the feverish tempo of his profession, the surprise isn’t that the School of Music was successful in luring him here, but that it succeeded in keeping him here as long as it did.

Badura-Skoda arrived in Madison in February 1966 — only moments after his 97-key grand piano had and mere hours before a scheduled recital. His previous concerts in Madison — in 1964 when he was a visiting professor of music and a return engagement in 1965 — had drawn large crowds. The 1966 concert, reportedly, was the largest, evoking comparisons to JFK’s visit in 1962. “The response at Wisconsin is very gratifying,” the pianist said. “We found a special interest in music here, not only among students but also in the population of the city.”

During his five-year residence, Badura-Skoda made frequent appearances in the Wisconsin Union Theater and Mills Music Hall, devoting entire programs to Beethoven and Schubert. Though he maintained a light teaching schedule in order to make long tours of North America, Europe and Asia, and to meet his extensive recording commitments, he finally succumbed, in 1971, to the frantic pace. In his dual roles as pianist and lecturer, Badura-Skoda knew his priorities. “I cannot afford to give up my international concert commitments, for if I did I would soon be forgotten as an artist.”

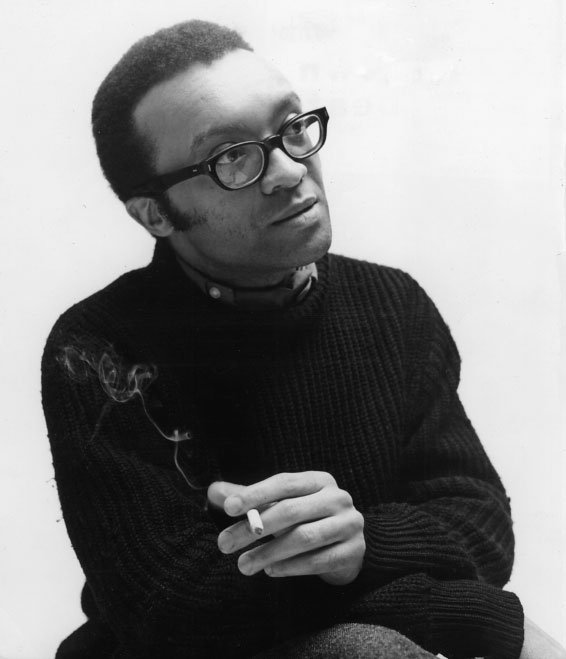

To witness the contrast of treatment given European classical pianists Johansen and Badura-Skoda and that applied to Cecil Taylor, a black avant-garde jazz pianist from Long Island, is to understand the asperity with which the Daily Cardinal editorialized in 1970. “His treatment,” the paper asserted, “by an inconsiderate, debased and incompetent staff of school officials has been demeaning … [and] criminal.”

Such denunciations were not limited to campus. Writing in the Wisconsin State Journal, Burt Levy added: “When seen in the context of the university, the Taylor experience is astounding.”

Coming to the university in 1969, Taylor’s acceptance by the jazz community was not yet complete. “In jazz no one was so persistently treated as a pariah for so long as Cecil Taylor,” said jazz critic Nat Hentoff.

But much like his performing career, where he was the object of intense interest but undermined by critics and club owners, Taylor attracted so many students to his black music seminars that an administrative limit of 800 students was imposed. Meanwhile, reports circulated that Taylor would be terminated at semester’s end.

Initially, Taylor was backed by students who petitioned for his retention; they achieved a modest success in gaining Taylor a limited one-year appointment. But Taylor’s gruff, racially polarizing opinions began to take their toll (the Capital Timesquoting him saying: “Black music! No honky can play it.”).

In his second year on campus, enrollment in his class had dropped to 30 students, two-thirds of whom he reportedly failed, and he announced plans to leave at the end of the school year. Before he did, the pianist-composer gave Madison a world premiere of a new three-part work. It went largely unappreciated.

© 1999

Stephen Andrew Miles